Vatican II

On This Day, Theology

10.11.2011

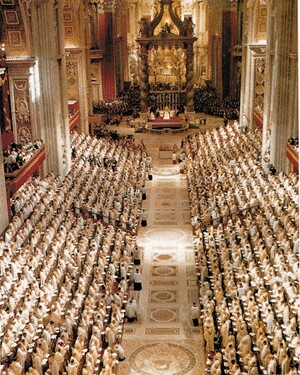

Today (October 11) is the anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council in 1962. Vatican II meant a lot of things to Roman Catholics on the ground (from changes in practices of fasting, to rumors that everything was about to blow wide open), but here is a theological overview of this epochal Roman Catholic event, as reported by Avery Dulles and Walter Kasper, according to me.

Today (October 11) is the anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council in 1962. Vatican II meant a lot of things to Roman Catholics on the ground (from changes in practices of fasting, to rumors that everything was about to blow wide open), but here is a theological overview of this epochal Roman Catholic event, as reported by Avery Dulles and Walter Kasper, according to me.Vatican II is such a major event for Roman Catholicism that twentieth-century Catholic theology can be instructively viewed in two movements: first, leading up to the council, and then developing from it. The rise of the “nouvelle theologie” in France (the big names are de Lubac, Bouillard, Daniélou, Congar, Chenu, Montecheuil, Dubarle, and even Teilhard de Chardin) is exemplary of the form taken by theological progress in the first half of the century: it was deeply rooted in a historical recovery of the grand tradition (especially Thomas and the Fathers, including the Eastern Fathers), open to revising ingrained Neo-Scholastic assumptions, and under constant scrutiny from a suspicious magisterium (in fact the name “new theology” was given to the movement by opponents charging it with innovation).

Avery Dulles once offered a list of ten basic teachings of Vatican II, which he considered to be “obvious to anyone seeking an unprejudiced interpretation of the council.” (The Reshaping of Catholicism, San Francisco, Harper & Row, 1988, 19-33).

Aggiornamento. Translatable as updating, adaptation, or even modernization, John XXIII’s catchword seems specifically designed to counter the hostility and suspicion of all things modern which had become characteristic of recent Catholicism. The council expresses great respect for the truth and goodness that modernization has brought with it, including the new humanism. The church should keep pace with the times, in order to enrich itself and better understand the treasures of Christ.

Reformability of the Church. The church is to be understood as the biblical People of God, which, though always sealed by the covenant, is nevertheless sometimes unfaithful. Since the Reformation, the idea of church reform has been understandably suspect to Catholics, but Vatican II harkened back to the earlier tradition of admitting, confessing, and repenting of abuses. The term “sinful church” remains off limits and distasteful, but “church of sinners” is appropriate.

Renewed Attention to the Word of God. After a period of neglect in which the Bible seemed to be a remote source of doctrine, Dei Verbum recovered the primacy of Scripture. The two-source theory was set aside in favor of a view of the teaching office which is “not above the word of God, but serves it, listening to it devoutly, guarding it scrupulously, and explaining it faithfully (DV 10).” This constitution also recommended the use of Scripture to all of the faithful, and called for a renewal of scriptural preaching.

Collegiality. Without denying the primacy of the pope, Vatican II did much to take apart the rigid pyramidal structure of the church. The pope is the head of the college of bishops, where all power in the church resides. Individual bishops are now seen as pastors in their own right, and even referred to as “vicars of Christ” (LG 28). This collegiality is expressed in many new institutions: the worldwide synod of bishops, conferences, diocesan pastoral councils, priests’ senates, etc. The quest is for structures that do justice to both pastoral authority as well as the spirit-filled community; neither an army nor a New England town meeting is a proper model.

Religious Freedom. Each person has religious freedom, and the right and duty to follow conscience with regard to religious belief: that this principle was endorsed by Roman Catholicism at Vatican II was not something self-evident, and was largely due to the influence of John Courtney Murray, whose advocacy of a religiously neutral state had previously called his orthodoxy into question.

Active Role of the Laity. Catholic Action, between the two wars, had managed to involve elite members of the congregation in the affairs of the apostolate of the hierarchy, but Vatican II went further than this by teaching the laity has an active apostolate in its own right as baptized believers. This is not simply a division of labor (clergy have a churchly mission, laity a secular), but a call for lay action “in the Church and in the world, in both the spiritual and the temporal orders” (AA 5)

Regional and Local Variety. Instead of emphasizing the universal church, Vatican II conceived of the church as a communion of particular churches, each under a “vicar of Christ,” its own bishop (LG 23). Speaking specifically of the difference between East and West, Vatican II said that diversity of customs and observances is an enrichment and not an obstacle to unity (UR 16).

Ecumenism. Anathema yielded to dialogue as the Catholic Church began to recognize in other Christian churches marks of truth and salvation, and accorded these heritages due reverence. Formal reunion seems a remote possibility at best, but ecumenical dialogue has led to greater mutual understanding, respect, and solidarity.

Dialogue with Other Religions. A corresponding shift took place in the attitude toward other religions: holding mission and dialogue in dynamic tension (rather than the antithesis that is often portrayed), the council called for respectful and mutual relationships of learning from each other, as well as the abiding necessity of missionary work so that Christ may be acknowledged among all peoples. Special attention was given to Jewish-Christian relations.

Social Mission of the Church. Working toward a just social order, while it has been on the modern Catholic agenda since at least the social encyclicals of Leo XIII, had previously been based on adherence to natural law. With Vatican II, the apostolate of peace and social justice began to appear as part of the church’s mission to carry on the work of Christ himself. The preferential option for the poor has its roots in the theme of the church’s special solidarity with them, mentioned in GS 1.

Implementation and Interpretation of the Council: Walter Kasper has described three phases in the reception of the council (“The Continuing Challenge of the Second Vatican Council,” in Theology and Church(New York: Crossroad, 1992)). The first phase was exuberant celebration, especially on the part of those who had been longing for change: the council seemed to be a complete new beginning, the start of an ongoing conciliar revolution in the church. The doors seemed to be flung wide open, and new ideas were advanced “in the spirit of the council” which went further than the documents themselves (167).

Inevitably, the next phase was characterized by disappointment, as collegiality and communio did not characterize the church at all levels, or in the radical way that some observers hoped for. Also, influenced by the general change of atmosphere in the 1970s, the church seemed to experience an identity crisis, a diffusion of the specifically Catholic, and church attendance and religious vocation declined. Conservatives and progressives squared off over against each other.

The third phase was officially inaugurated on January 25, 1985, when John Paul II convened an extraordinary synod of bishops to discuss the reception and interpretation of the council, an official admission that implementing the council was a task yet to be accomplished.

One of the most important challenges in reaching this goal is developing a hermeneutic of the conciliar statements: how are we to read them? This is a thorny problem for three reasons: 1. Vatican II issued no condemnations, so its positive declarations cannot be sharpened by polemical definition. 2. John XXIII deliberately gave the council a pastoral tone, rather than a dogmatic or disciplinary/legal tone; pastoral statements are harder to interpret. 3. The documents contain purely formal compromises between conservative and progressive statements, which stand side by side and unreconciled. There is especially “a juxtaposition, a double viewpoint, a dialectic, if not actually a contradiction between two ecclesiologies” (170), the hierarchical and the communio model.

There is a kind of reversal in the constitution of the so-called progressive and conservative parties: the council’s “progressives” were in fact the representatives of the greater and wider tradition as oppposed to its levelling and simplification in neo-scholasticism, while the “conservatives” were mainly interested in upholding recent tradition, especially Vatican I. In this situation, Vatican II followed the standard conciliar method of reconciliation: it described the limits of the church’s position on either extreme, but did not generate a comprehensive theory to explain their unity. As usual, this theoretical mediation is the task of post-conciliar theology.

According to Kasper, this situation suggests four hermeneutical principles for the doctrinal statements: 1. the texts must be understood as a whole, with constitutive tensions. 2. The letter and spirit of the council must be understood as a unity. 3. The council must be viewed in light of the wider tradition, rather than as the watershed between an old church and a new church. 4. The continuity of what is Catholic is to be understood as a unity between tradition and a living, relevant interpretation in the light of the current situation (171-2).

No comments:

Post a Comment